Our private hospitals are no small enterprises. They sit on the cities’ main arteries, and their windows command great views. They are purpose-built; their interiors are fully equipped; their services are nearly perfect; and the teams who run these set-ups are highly skilled professionals. Yet, these sumptuous settings fail to give our patients the impression of the level of care that one would have imagined. The patients believe, in fact, that they have been misdiagnosed, wrongly treated, or in some cases, outright cheated, even though they had received the best possible treatment. While patients go home with this image of healthcare in their minds, we think the services we render are flawless and continue our work without a clue about our patients’ feelings. If we are so confident about our services, how is it possible, then, that our patients think so differently from their healthcare teams? What is this gap? Is it possible that both parties—healthcare and patients—are doing their best in their own way; it is just that their efforts fail to overlap, thus creating no area of mutual trust?

Before we move on to identify the causes for this gap, we need to stop blaming the patients for a moment. Then, and only then, can we understand what we need to improve on our side. Of course, patients have their problems. Low income and reluctance to spend money on health, social pressure against using modern medicine, and illiteracy spiced with haughtiness on the part of the patient—all these are actual roadblocks in the way of delivering good medical care. Fixing these socio-economic barriers would require a private-public partnership. Therefore, in this essay, let us focus on identifying the lapses in our approach toward patient care that the private sector can improve alone, whether a hospital, a polyclinic, or even a solo physician.

Table of Contents

One-time, one-dimensional patient evaluation

The problem starts with the fact that the patient-physician relationship never gets past the stage of strangeness. The patient rarely receives the welcome and warmness he expects from his healer. Rather, as a rule, the physician declares the previous prescriptions and test results shady, conveying it in a tone as if it was the patient’s fault all along to have seen those previous doctors. Any question by the patient produces a choleric answer from the other side of the table. Finding himself in this socially awkward position, feeling discouraged, he loses the will and interest to share his story, keeping to himself what he feels and thinks about his illness. This hesitation on the part of the patient deprives the physician of not only important clinical information. It also keeps him from understanding who his patient is, the patient not in the sense of just a sick body, but the patient as a person—a complex, living, breathing, social being who exists not in a vacuum but lives an intricate life among other humans. This first meeting between our patients and physicians, which mostly also proves to be the last, a meeting which I have come to describe as a “one-time, one-dimensional patient evaluation,” fails to establish any meaningful and long-term relationship. In the end, it leaves both parties dissatisfied, the physician for not knowing his patient and the patient for not being understood.

Lack of comprehensive care

Thus, seeing a patient with this limited view in a cold, calculated manner, how can a physician be expected to provide comprehensive care? By comprehensive care, I mean a complete evaluation of the patient during a single visit. Such a thorough assessment asks a doctor of his time, energy, and emotions. In the world’s leading healthcare systems, teams make every effort to gather a patient’s data that helps the doctor understand the patient’s clinical picture even before his arrival. And if some information is amiss, the doctor doesn’t hesitate to call the patient’s other doctors to clear the picture further. This thorough review before the patient’s arrival not only helps break the ice between the two strangers on their first meeting but also creates a sense of familiarity as if they both have known each other before. Consequently, when the patient finally meets the doctor, genial and compassionate, it helps build patient-physician trust, without which there can be no two-way communication. In our settings, no such “connection” thing exists. No efforts are made to learn about the patient, make any connection, or show any compassion. How on earth, one wonders, a system works where a completely unknown patient gets his diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up plan within a few minutes? Perhaps, this is the reason why our physicians never mention the diagnosis (how can they if they don’t have one), our patients don’t feel better (how can they, except through the placebo effect), and none of the parties show any interest in follow up (follow up for what?).

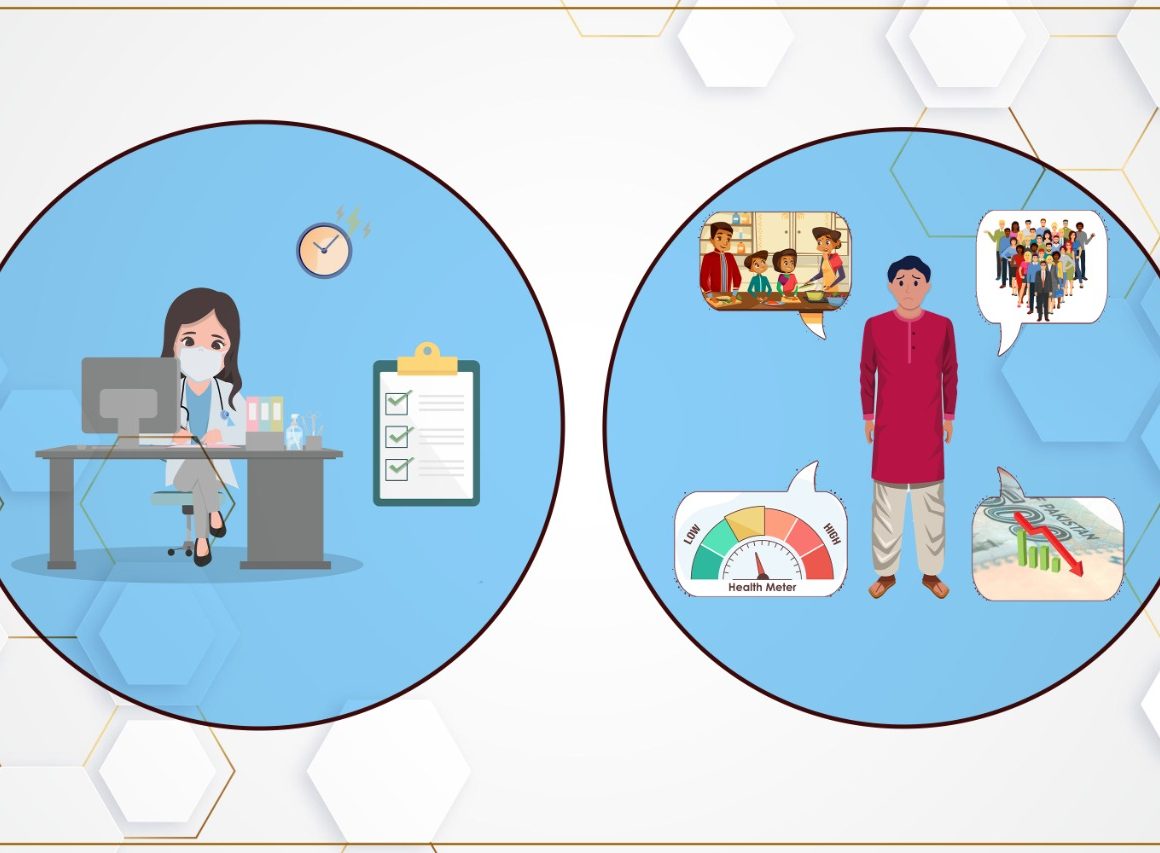

Lack of integrated health

A system that can’t afford comprehensive health might have, logically speaking, leaned heavily on integrated health. Integrated health? In the twenty-first century, the medical field has budded into entirely different but overlapping specialties, each specialty offering something exclusive to a patient’s care. Though such care is fragmented, placing a considerable burden on a patient’s shoulder, who often feels overwhelmed due to the number of appointments alone. Despite this fact, it is the best way to deliver healthcare. Therefore, great healthcare systems across the globe make every effort to give their patient the most specialized care, trying at the same time to achieve this goal with as much inconvenience for the patient as possible, using electronic medical records, providing transport, arranging home health visits, and now putting at the center of all these efforts Telemedicine. In Pakistan, on the other hand, the idea of integrated health or specialized care remains in its infantile stages, continuously crying for support, and nutrition but getting no attention. Of course, we lack the number of specialists to build an ideal integrated system. The question is, how well are we incorporating the ones who are available. With a few exceptions, the concept of referral to a sub-specialist remains quite unknown. This practice of doctors keeping their patients away from other specialists results both from ignorance and dereliction. Most of our general physicians never learn when to ask for help, failing to realize that sometimes giving the best care to their patients means simply referring them to experts, doctors who can better manage the illness. Sometimes, physicians can’t resist the system and deliberately discourage the referrals, even though it costs the patient sacrifice and suffering. This is how it is, they say. Consequently, in a prototype prescription in Pakistan, you will find a list of medications and lab tests, occasionally a diagnosis, and even a follow-up plan, but never a referral to another specialist.

Lack of follow-up

Lastly, our system shows no interest in follow-up, missing even this last opportunity to establish a connection with the patient. At best, our notion of follow-up rarely extends beyond asking the patient to come back after a certain time period. We scarcely put any effort into using all the latest technology—phones, computers, the internet, and telemedicine—which can certainly enhance the follow-up rate. Dissatisfied, patients use the prescription for a few days and then try another doctor, bouncing from one physician to another, wasting weeks and months through useless appointments and harmful medicines, living through the fear of unidentified illness as well as pain from the actual disease.

Conclusion

We can see a palpable architectural evolution of our hospitals and clinics, but our clinical practice and attitude show no signs of improvement. This stagnation screams off our prescription pads, which have barely changed in their style or outlook in the last seven decades. The rudeness and superiority that our physicians and their assistants never fail to display have changed only slightly. As regards customer service, our performance is highly pathetic. We expect patients to assume all the responsibility, from buying their medications to arranging follow-ups, from organizing their prescriptions to understanding their medicines. In short, if we are to deliver the benefits of modern medicine to our patients, we need an immediate change in our healthcare. Ignoring these errors can have long-term consequences, particularly trust issues, and thus call for immediate redress in architecture, practice, behavior, and work. This mistrust between healthcare and the patient may not affect one hospital’s financial scores, but it does undermine the patients’ trust in the entire healthcare system.

Despite these observations, I have a confession to make. Our patient-physician relationship, which has been like this since I came of age, and which I have the honor to observe both as an insider(working in Pakistan) and outsider(being away from it for ten years), has barely evolved. Two things never cease to surprise me though. Our healthcare makes no effort even to pretend that it cares for the patient and, still, remains under the illusion that it is giving its best. On the other side, our patients’ list of expectations from healthcare continues to grow.

Perhaps, deep down, we all want to know what would be the reaction of patients when they see a doctor with a smiling face and empathic behavior!